Two more titans of their respective genres face off: The magical score for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by the ever-impressive John Williams against Ennio Morricone’s masterpiece music for the 1986 film The Mission. This may be a case of high art versus appealing to the masses. Let us begin as usual with the higher seeded entry. Harry Potter is the epitome of scoring that tells a story, eliciting a strong emotional response, as the intended audience of the film is children and families, for whom the themes of the film must be clearly accentuated by the music. For Williams, working again with director Christopher Columbus as they had done on Home Alone, the subject matter was of a familiar nature which allowed Williams to compose music neatly within his comfort zone. As a result, the score features stylistic similarities with both past and future works. As a composer frequently attached to franchises, Williams established much core thematic material in this score to be developed and extended in his later scores to Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. After those two films different directors brought in different composers and, regrettably but understandably, something of the original content and, dare I say it, magic, was lost. The later films took darker turns and the music followed in turn – one day I will write a review of Alexandre Desplat’s music for the last two films, as I believe them to be the best examples of the darker music present for the franchise in its later years.

Let us begin as usual with the higher seeded entry. Harry Potter is the epitome of scoring that tells a story, eliciting a strong emotional response, as the intended audience of the film is children and families, for whom the themes of the film must be clearly accentuated by the music. For Williams, working again with director Christopher Columbus as they had done on Home Alone, the subject matter was of a familiar nature which allowed Williams to compose music neatly within his comfort zone. As a result, the score features stylistic similarities with both past and future works. As a composer frequently attached to franchises, Williams established much core thematic material in this score to be developed and extended in his later scores to Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. After those two films different directors brought in different composers and, regrettably but understandably, something of the original content and, dare I say it, magic, was lost. The later films took darker turns and the music followed in turn – one day I will write a review of Alexandre Desplat’s music for the last two films, as I believe them to be the best examples of the darker music present for the franchise in its later years.

However, for The Philosopher’s Stone, Williams returned to the composing style of his heyday in the 80s – many moments of the score sound reminiscent of Star Wars, E.T., Indiana Jones, Hook, and Home Alone. Williams is a master of both scoring magical subject matter and capturing a sense of the world from a child’s perspective, and the iconic main theme for Harry Potter, ‘Hedwig’s Theme’ is a testament to this skill. The melodies in this composition have become so ingrained into modern popular culture that anyone born in the 1990s and 2000s can recognise and identify this theme. Williams crafted two phrases, both of which are played on the celeste and horns in ‘Hedwig’s Theme’. The A-phrase is Hedwig’s motif, which represents the magical wizarding world, and is also the motif carried through the entire franchise – it is often light and wondrous. The B-phrase is for Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, a more noble and robust motif. Each motif present in this waltz captures the essence of the darkly alluring wizarding world of Harry Potter, whilst remaining light and memorable enough for all ages.

However, for The Philosopher’s Stone, Williams returned to the composing style of his heyday in the 80s – many moments of the score sound reminiscent of Star Wars, E.T., Indiana Jones, Hook, and Home Alone. Williams is a master of both scoring magical subject matter and capturing a sense of the world from a child’s perspective, and the iconic main theme for Harry Potter, ‘Hedwig’s Theme’ is a testament to this skill. The melodies in this composition have become so ingrained into modern popular culture that anyone born in the 1990s and 2000s can recognise and identify this theme. Williams crafted two phrases, both of which are played on the celeste and horns in ‘Hedwig’s Theme’. The A-phrase is Hedwig’s motif, which represents the magical wizarding world, and is also the motif carried through the entire franchise – it is often light and wondrous. The B-phrase is for Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, a more noble and robust motif. Each motif present in this waltz captures the essence of the darkly alluring wizarding world of Harry Potter, whilst remaining light and memorable enough for all ages.

Like any Williams score, motifs for other places and people feature throughout the score. A fast paced horn theme of a similar melodic structure to the B-phrase of ‘Hedwig’s Theme’ is Williams’ ‘flying theme’, which is often associated with Quidditch, the infamous broomstick-based sport of Harry Potter. It has a wonderful string-based secondary phase, heard at 3:30 of ‘Hedwig’s Theme’ that has a majestic and highly appealing quality to it. A fourth theme for Harry, his friendship with Ron and Hermione, and his distant relationship to his dead parents, forms the core of the ‘Harry’s Wondrous World’ suite, a true score highlight. It is reminiscent of the more patriotic and celebratory music Williams has written for Americana, whilst still retaining that optimism inherent within childlike wonder. Building from this, a fifth, more restrained and melancholic theme exists for the sadder moments of the film that focus on loss. It crops up here and there in the score, but it’s greatest rendition is in the penultimate track ‘Leaving Hogwarts’, where the delicate string, celeste, and percussion orchestrations never fail to send shivers down my spine. Finally, a 7 note motif exists for Voldemort and all things generally mysterious and spooky about Hogwarts, heard most prominently in ‘The Gringotts Vault’.

Like any Williams score, motifs for other places and people feature throughout the score. A fast paced horn theme of a similar melodic structure to the B-phrase of ‘Hedwig’s Theme’ is Williams’ ‘flying theme’, which is often associated with Quidditch, the infamous broomstick-based sport of Harry Potter. It has a wonderful string-based secondary phase, heard at 3:30 of ‘Hedwig’s Theme’ that has a majestic and highly appealing quality to it. A fourth theme for Harry, his friendship with Ron and Hermione, and his distant relationship to his dead parents, forms the core of the ‘Harry’s Wondrous World’ suite, a true score highlight. It is reminiscent of the more patriotic and celebratory music Williams has written for Americana, whilst still retaining that optimism inherent within childlike wonder. Building from this, a fifth, more restrained and melancholic theme exists for the sadder moments of the film that focus on loss. It crops up here and there in the score, but it’s greatest rendition is in the penultimate track ‘Leaving Hogwarts’, where the delicate string, celeste, and percussion orchestrations never fail to send shivers down my spine. Finally, a 7 note motif exists for Voldemort and all things generally mysterious and spooky about Hogwarts, heard most prominently in ‘The Gringotts Vault’.

Elsewhere in the score, several secondary motifs exist, but their performances are limited to individual scenes or are tied in some way to the more prominent motifs. The music for the Quidditch match is reminiscent of the pod-racing parade sequence from Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, and other action sequences are familiar in nature to Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. The lighter material is reminiscent of Home Alone, and the more lively and exciting sequences recall Hook. Realistically, though, even if you accept that parts of this score exhibit Williams on auto-pilot, the music that comes from the composer even at those times is superior to most of what comes from the rest of the industry, and The Philosopher’s Stone functions very well as the foundation for the subsequent two sequel scores. The sheer quality and thematic brilliance of the music, drenched in Williams’ signature orchestrations, are more than enough to label it as a modern classic.

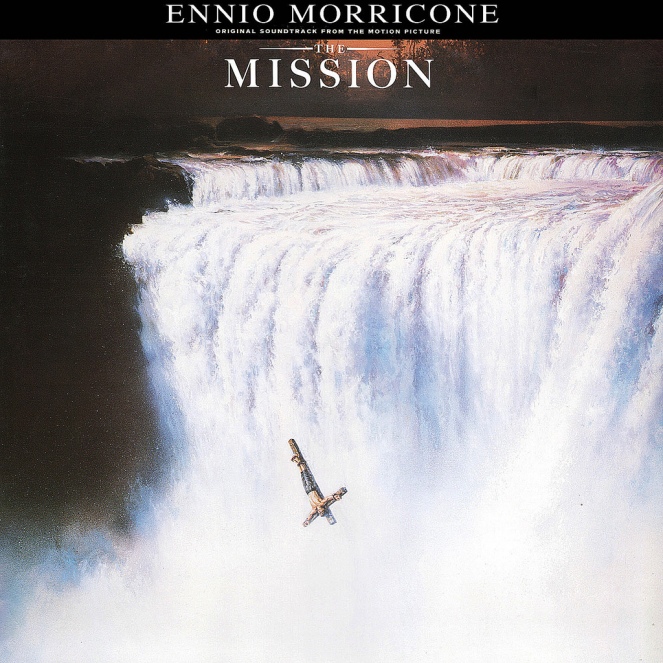

Elsewhere in the score, several secondary motifs exist, but their performances are limited to individual scenes or are tied in some way to the more prominent motifs. The music for the Quidditch match is reminiscent of the pod-racing parade sequence from Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, and other action sequences are familiar in nature to Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. The lighter material is reminiscent of Home Alone, and the more lively and exciting sequences recall Hook. Realistically, though, even if you accept that parts of this score exhibit Williams on auto-pilot, the music that comes from the composer even at those times is superior to most of what comes from the rest of the industry, and The Philosopher’s Stone functions very well as the foundation for the subsequent two sequel scores. The sheer quality and thematic brilliance of the music, drenched in Williams’ signature orchestrations, are more than enough to label it as a modern classic. Ennio Morricone’s score to The Mission is, once again, a very different animal to its competitor. Where Harry Potter appeals almost universally, on the surface some may find The Mission a far less relatable score, and will have difficulty getting into its subject and style. The film, although lauded by critics, was not a box office success. The convoluted plot concerning the efforts of Jesuit missionaries to convert the Guarini people, and subsequently defend them from the Spanish and Portuguese, political and ecclesiastical machinations, and large amounts of introspective scenery footage alienated audiences from the core story. However, Ennio Morricone’s score for the The Mission vastly outstripped the legacy and fame of the film for which it was written, and in the intervening thirty years has gone on to be lauded as one of the most significant film scores written during the 1980s. Trying to pinpoint what makes Morricone’s score so wonderful is almost a futile exercise, but I’ll start where most people start: with the motifs.

Ennio Morricone’s score to The Mission is, once again, a very different animal to its competitor. Where Harry Potter appeals almost universally, on the surface some may find The Mission a far less relatable score, and will have difficulty getting into its subject and style. The film, although lauded by critics, was not a box office success. The convoluted plot concerning the efforts of Jesuit missionaries to convert the Guarini people, and subsequently defend them from the Spanish and Portuguese, political and ecclesiastical machinations, and large amounts of introspective scenery footage alienated audiences from the core story. However, Ennio Morricone’s score for the The Mission vastly outstripped the legacy and fame of the film for which it was written, and in the intervening thirty years has gone on to be lauded as one of the most significant film scores written during the 1980s. Trying to pinpoint what makes Morricone’s score so wonderful is almost a futile exercise, but I’ll start where most people start: with the motifs. Three major motifs form the cornerstone of this score. The first relates to the mission itself, the effort by Jesuit missionaries to convert the native Guarini population of South America. It is heard in the opening track ‘On Earth as It Is in Heaven’, which is actually the end titles sequence of the film. The theme is rhythmic, for harpsichord and Latin choir initially, and then with added tribal percussion and counterpointing from Gabriel’s oboe (more on that later) and Latin chanting. In this way the theme cleverly speaks to the culture clash between Western Christianity and the Guarini. The second major theme is for the Iguazu Falls, the modern border for Brazil and Argentina, and a centre of major cultural importance for the Guarini. The melody is stunningly beautiful in its simplicity, as is the orchestration, with strings, harp, a calming pan-flute element, and plucked bass. This gradual swells into a spine-chilling full orchestral performance, with resolute brass counterpoint, and then gradually fades away again. Sublime.

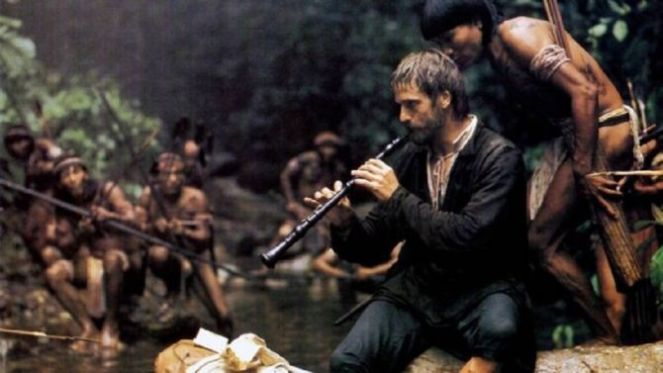

Three major motifs form the cornerstone of this score. The first relates to the mission itself, the effort by Jesuit missionaries to convert the native Guarini population of South America. It is heard in the opening track ‘On Earth as It Is in Heaven’, which is actually the end titles sequence of the film. The theme is rhythmic, for harpsichord and Latin choir initially, and then with added tribal percussion and counterpointing from Gabriel’s oboe (more on that later) and Latin chanting. In this way the theme cleverly speaks to the culture clash between Western Christianity and the Guarini. The second major theme is for the Iguazu Falls, the modern border for Brazil and Argentina, and a centre of major cultural importance for the Guarini. The melody is stunningly beautiful in its simplicity, as is the orchestration, with strings, harp, a calming pan-flute element, and plucked bass. This gradual swells into a spine-chilling full orchestral performance, with resolute brass counterpoint, and then gradually fades away again. Sublime. However, it is the third theme that gains the score its fame and notoriety: Gabriel’s Oboe. Initially it is performed on screen by Jeremy Irons’ character Father Gabriel. Morricone wrote the melody after watching Irons’ random finger improvisations on an oboe on screen, and matched it to the footage as if Irons had been playing the melody all along. Who knows what that might have sounded had Irons been actually playing the oboe, but the resulting motif is haunting, beautiful, and evocative. How such a melody could have been written in this manner is truly astonishing. In the album track the simple harpsichord rhythm, matching ‘On Earth as It Is in Heaven’, and string accompaniment is entrancing, capturing the essence of Gabriel’s peaceful, gentle nature. The many different subsequent adaptations and re-orchestrations of this theme, ranging from transposed solo instruments such as cello and violin to full scale orchestral and choral arrangements by the likes of Andre Rieu and Morricone himself, earmark this melody as a timeless and masterful composition.

However, it is the third theme that gains the score its fame and notoriety: Gabriel’s Oboe. Initially it is performed on screen by Jeremy Irons’ character Father Gabriel. Morricone wrote the melody after watching Irons’ random finger improvisations on an oboe on screen, and matched it to the footage as if Irons had been playing the melody all along. Who knows what that might have sounded had Irons been actually playing the oboe, but the resulting motif is haunting, beautiful, and evocative. How such a melody could have been written in this manner is truly astonishing. In the album track the simple harpsichord rhythm, matching ‘On Earth as It Is in Heaven’, and string accompaniment is entrancing, capturing the essence of Gabriel’s peaceful, gentle nature. The many different subsequent adaptations and re-orchestrations of this theme, ranging from transposed solo instruments such as cello and violin to full scale orchestral and choral arrangements by the likes of Andre Rieu and Morricone himself, earmark this melody as a timeless and masterful composition. These motifs develop and are refined in various sequences, such as in ‘Vita Nostra’ tribal percussion accompaniment and counterpointed chanted “mission” theme, and the slow and steady rendition of the “falls” theme on strings in ‘Climb’, darker variation for low strings in ‘Remorse’, and gentle peacefulness with flute trilling to represent fluttering birds in ‘The Mission’. There is also a secondary theme highlighted in ‘Brothers’, for the converted missionary Mendoza and his brother Felipe, a gentle, sentimental theme for guitar, flute, and strings. The betrayal that tears them apart is addressed in ‘Carlotta’ with darker guitar plucking. Action and tension dominate the rest of the score, with throbbing bassoons, swirling strings, brass accents and rumbling percussion. The conclusive ‘Miserere’ is a beautiful solo boy soprano performance of the “mission” theme. If that wasn’t enough, Morricone also wrote two pieces of liturgical choral music, ‘Ave Maria Guarini’ and ‘Te Deum Guarini’, both performed by a solo choir of South American natives with such ragged and raw yet deeply spiritual authenticity that you almost can’t believe it was written in the 1980s.

These motifs develop and are refined in various sequences, such as in ‘Vita Nostra’ tribal percussion accompaniment and counterpointed chanted “mission” theme, and the slow and steady rendition of the “falls” theme on strings in ‘Climb’, darker variation for low strings in ‘Remorse’, and gentle peacefulness with flute trilling to represent fluttering birds in ‘The Mission’. There is also a secondary theme highlighted in ‘Brothers’, for the converted missionary Mendoza and his brother Felipe, a gentle, sentimental theme for guitar, flute, and strings. The betrayal that tears them apart is addressed in ‘Carlotta’ with darker guitar plucking. Action and tension dominate the rest of the score, with throbbing bassoons, swirling strings, brass accents and rumbling percussion. The conclusive ‘Miserere’ is a beautiful solo boy soprano performance of the “mission” theme. If that wasn’t enough, Morricone also wrote two pieces of liturgical choral music, ‘Ave Maria Guarini’ and ‘Te Deum Guarini’, both performed by a solo choir of South American natives with such ragged and raw yet deeply spiritual authenticity that you almost can’t believe it was written in the 1980s. With such music, Morricone describes to us the vast, beautiful, unspoiled Amazon jungle, the humility of the Jesuits, their compassion for the Guarini, and the contrasting disdain of the Spanish and Portuguese. He juxtaposes scenes of violence and martyrdom with graceful choirs and beautiful orchestrations. His work has remained popular for decades with the general public and the classical world, transcending the film for which it was written. Something about The Mission, and especially Gabriel’s Oboe and the “falls” theme, is intangibly appealing. The listener may not be religious, but Morricone is, and the film’s religious themes clearly inspired him to musically express that religious devotion with an exceptional level of skill and heart. Morricone also employs such compositional excellence on The Mission. His ability to juxtapose, counterpoint, write contrapuntally and orchestrate to convey complicated, sometimes conflicting, emotional nuances and sentiments is clearly intellectual and consistently superb. The fact that his music lost out on the Academy Award to Herbie Hancock’s 15 minutes of original music for Round Midnight is one of the biggest miscarriages of justice in the history of film music.

With such music, Morricone describes to us the vast, beautiful, unspoiled Amazon jungle, the humility of the Jesuits, their compassion for the Guarini, and the contrasting disdain of the Spanish and Portuguese. He juxtaposes scenes of violence and martyrdom with graceful choirs and beautiful orchestrations. His work has remained popular for decades with the general public and the classical world, transcending the film for which it was written. Something about The Mission, and especially Gabriel’s Oboe and the “falls” theme, is intangibly appealing. The listener may not be religious, but Morricone is, and the film’s religious themes clearly inspired him to musically express that religious devotion with an exceptional level of skill and heart. Morricone also employs such compositional excellence on The Mission. His ability to juxtapose, counterpoint, write contrapuntally and orchestrate to convey complicated, sometimes conflicting, emotional nuances and sentiments is clearly intellectual and consistently superb. The fact that his music lost out on the Academy Award to Herbie Hancock’s 15 minutes of original music for Round Midnight is one of the biggest miscarriages of justice in the history of film music. The Mission is a genuine masterpiece. It is a perfect combination of everything that can possibly make a film score great. It fits the film, carrying a dramatic narrative and elevating it to the point of inseparability from the film, and it is excellent as pure music in everything from recurring themes that develop through the score to orchestration, technique, and those intangibles of “beauty” and “memorability”, subjective, but wide-ranging. Truly, Harry Potter has thematic brilliance and memorability too, but much of it is Williams referencing his older material from a comfort zone, good as it may be. Despite its popularity, Harry Potter doesn’t really hold a holy scented candle to The Mission.

The Mission is a genuine masterpiece. It is a perfect combination of everything that can possibly make a film score great. It fits the film, carrying a dramatic narrative and elevating it to the point of inseparability from the film, and it is excellent as pure music in everything from recurring themes that develop through the score to orchestration, technique, and those intangibles of “beauty” and “memorability”, subjective, but wide-ranging. Truly, Harry Potter has thematic brilliance and memorability too, but much of it is Williams referencing his older material from a comfort zone, good as it may be. Despite its popularity, Harry Potter doesn’t really hold a holy scented candle to The Mission.

Sorry John Williams fans! I love Harry Potter too, I promise!

NEXT WEEK: Pirates of the Caribbean (#8) vs. Chariots of Fire (#9)